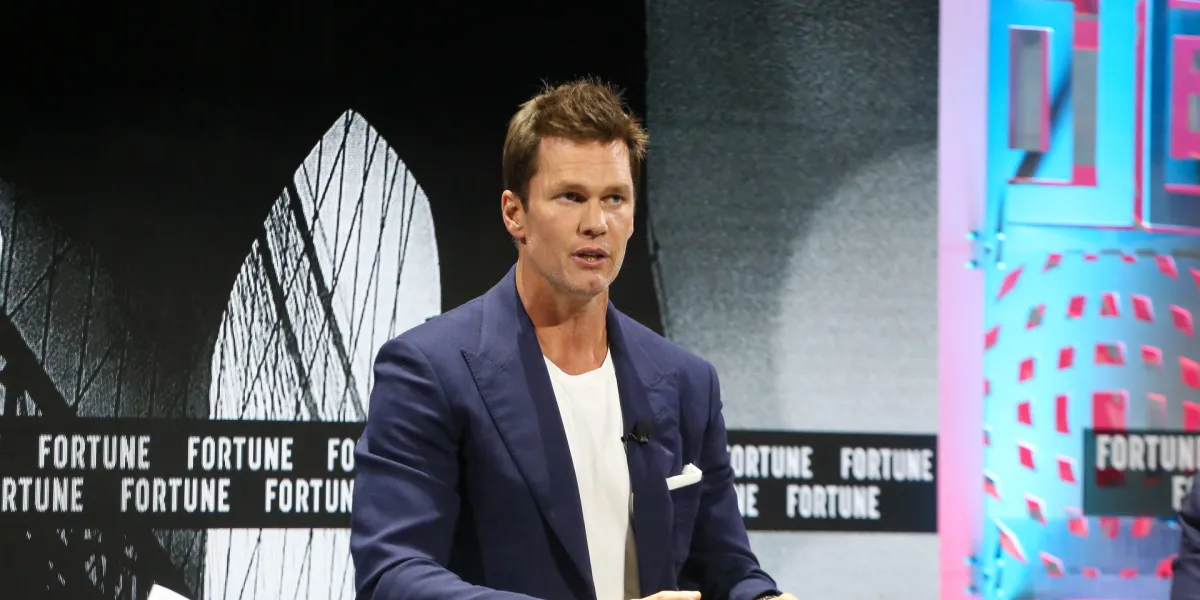

Tom Brady was speaking to some 200 CEOs, telling them how he became football’s greatest quarterback of all time. He was at the recent Fortune Global Forum in New York City, but he made only fleeting connections between his career and the CEOs’ jobs. That was clearly fine with the CEOs. He’s a football god with a great story to tell, and just hearing it was a thrill.

Still, let’s hope the CEOs listened carefully. Whether they knew it or not, Brady’s story of a football career was a detailed tutorial on great performance at a CEO’s job. Decades of research have produced a prescription for excellent performance in any domain, and Brady’s life-long football experience matched that prescription exactly. While everyone’s story is unique, the factors that built Brady’s skills over several years are not. Research has shown that those same factors are the key to world-class performance broadly. It isn’t quick or easy; there is no magic. But what worked for Brady really does work for all of us in all we do.

The essence of his story is that he wasn’t a child prodigy quarterback, not a natural star—just the opposite. Review his journey to greatness and see if you notice a pattern:

· In high school “I was the backup quarterback on a freshman football team that didn’t win a game,” he said. “We sucked so bad, and they still wouldn’t put me on the field.” He became the starter as a sophomore because the previous starter decided he’d rather play basketball. Crucially, Brady “consulted a mentor of mine who taught me how to throw the football. Every single summer I’d go to his camp. I would continue to work on mechanics and techniques on my own.”

· He became good enough for the University of Michigan to recruit him, but as a freshman he was the team’s seventh-ranked quarterback. By the end of the year he had moved up to fourth. In the next year he worked his way up to third, then second. Through the year after that he remained the backup. In his fourth year he had to compete with a new recruit to become the starter, and he won that competition. Yet in his fifth year he again had to compete with another quarterback, finally becoming the starter in the season’s second half. In his thrilling final college game his team beat Alabama, coming back from two 14-point deficits.

· “Everyone must see now, at this point, I’m going to be a great NFL quarterback,” he recalled. “Nope. No way.” In the NFL draft he was the 199th pick, going to the New England Patriots, which he joined as the fourth-ranked quarterback. In his first year he worked his way up to third, in the next year up to second. Then the starting quarterback was badly injured and out for the season. Brady went in as the starter, “and I never went off the field after that.” At age 24, after ten years of intensive fighting his way up, he remained the starting quarterback for 19 seasons with the Patriots and three seasons with the Tampa Bay Buccaneers, winning a record seven Super Bowls and becoming the undisputed GOAT, the greatest of all time.

Brady was doing what the researchers call deliberate practice. It’s specifically defined and not practice as most of us conceive it. Its central feature is that it continually pushes you just beyond, but not way beyond, your current limits. You can’t improve if you practice only what you can already do, and you’re simply lost if you reach too far. As you improve, your practice must change, so you’re always forcing yourself to do what you can’t quite do. That’s what Brady was doing as he steadily climbed the multi-step ladder from backup high school quarterback to starting NFL quarterback to the greatest NFL quarterback.

Deliberate practice requires other elements as well. It must be repeated a lot, which eventually alters your brain, and you must receive continuous feedback. Brady met those requirements in high school with the mentor who taught him how to throw and then with high-level coaches at Michigan and in the NFL.

One more thing about deliberate practice: It isn’t fun. Hank Haney, Tiger Woods’s coach for several years, says Tiger was an example of deliberate practice, which Haney calls “the most difficult and highest level of practice because it requires painstaking focus on weaknesses…. The great improvers are willing to get uncomfortable and make the mental and physical effort to correct a flaw.” Brady was given ideal circumstances for deliberate practice, but he couldn’t have become great without a powerful inner drive that he had to find deep in himself.

Deliberate practice can even build leadership, though not in a way people might imagine. Brady’s team leadership was as important in his career as his own performance. His Patriots teammates elected him team captain for 18 seasons, and he was co-captain for two seasons with the Buccaneers. The reason goes to the essence of deliberate practice, the imperative of making oneself uncomfortable. “I played with a lot of athletes, and part of my role as a leader was to make these guys feel uncomfortable,” he said. “As great as they were, I was always focused on making sure they were working harder than they ever thought they could work.”

That’s the message Brady wanted those 200 CEOs to remember. “Hopefully you find people you love to work with, you push each other to succeed, you push each other outside your comfort zone,” he told them. “It’s okay to feel uncomfortable. Unless we stress our mind, it doesn’t grow.”