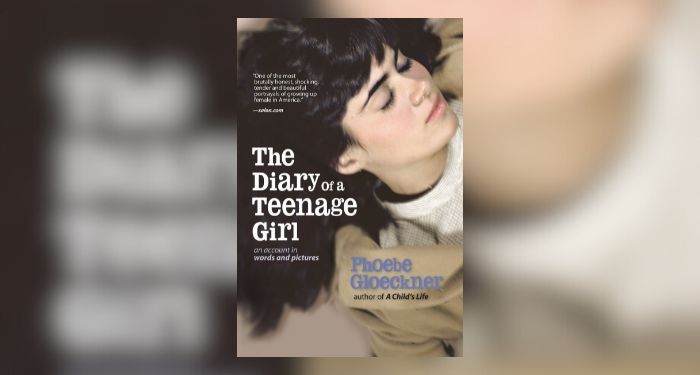

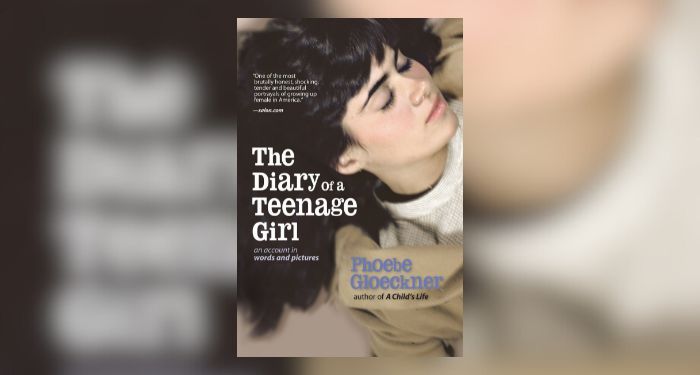

Half autofiction, half graphic novel, this book follows a particularly dramatic year in Minnie Goetze’s life. At 15, she’s bursting with newly acquired knowledge. San Francisco in the 1970s still carries the reputation it got in the 1960s as a haven for the hippies, artists, and the itinerant. The book opens with her reminiscing about losing her virginity to her mother’s boyfriend earlier that day. Minnie longs to tell her mother about this and tries to process it, but she knows that she has to keep the relationship a secret. Not only is Monroe cheating on Minnie’s mother with her, it’s a deeply inappropriate relationship.

She starts to also explore sex with boys her own age, but the experiences aren’t any better. She also starts doing drugs with her friend Kimmie. Throughout all this drama, Minnie is skipping school and gets kicked out for her low attendance rate. Her life spins even more out of control, driven by drugs and a general lack of caring adults in her orbit.

The darkness of the subject matter is so well-handled. Gloeckner’s diaries, which are part of this book, add immediacy to the narrative. It really does feel like a diary. It’s not entirely made up of her diaries, though. The comics portions of the story present a clear adult perspective on the story. Monroe is drawn to look like what he is: a creep preying on a young teenage girl. The comics act as a meta-commentary of Minnie’s possible future interpretations of her own life. She even writes to famous artist Aline Kominsky-Crumb about her life and how she wants to pursue art.

The diary with comics reads as a method of processing the traumas of her childhood. At the same time, Minnie is thrilled by the new experiences she encounters. She’s left alone to wander the streets of San Francisco. Her mother is distant at best, while the older men in her life are controlling. Outside of Monroe, she also keeps in touch with another ex of her mother’s, who has strong opinions about how Minnie should live her life.

Though the content is difficult, Minnie is a compelling narrator and the heart-on-your-sleeve nature of her teenage brain is fantastic. When she realizes how poorly she’s been treated and stands up for herself, it’s entirely cheer-worthy. The moment is smaller and more realistic than other work focused on young adults, but that’s what makes this book great. The most bombastic moments of a young person’s life can appear to be small when they’re happening. But looking back, they mean everything.

Phoebe Gloeckner’s writing is thoughtful and deep, and her comics are highly detailed—her time as a medical illustrator is a clear influence on the art. I find this book to be sort of lightning in a bottle. It presents teenage drug use and childhood sexual abuse matter-of-factly but doesn’t sensationalize. There’s depth to Minnie’s exploration and her growth is extremely moving.

Whether comics count as serious literature is a regular argument. Comics don’t have to be serious and important literature in order for reading comics to be respectable, but comics are their own expressive artform that allow a different form of storytelling. In using her teenage diary and fictionalizing it, Phoebe Gloeckner employed comics to provide perspective.

The dedication of the novel reads “for all the girls when they have grown.” When you look back on your teenage experiences, you may be both thrilled and disgusted. But it’s your story, and you get to tell it how you want.