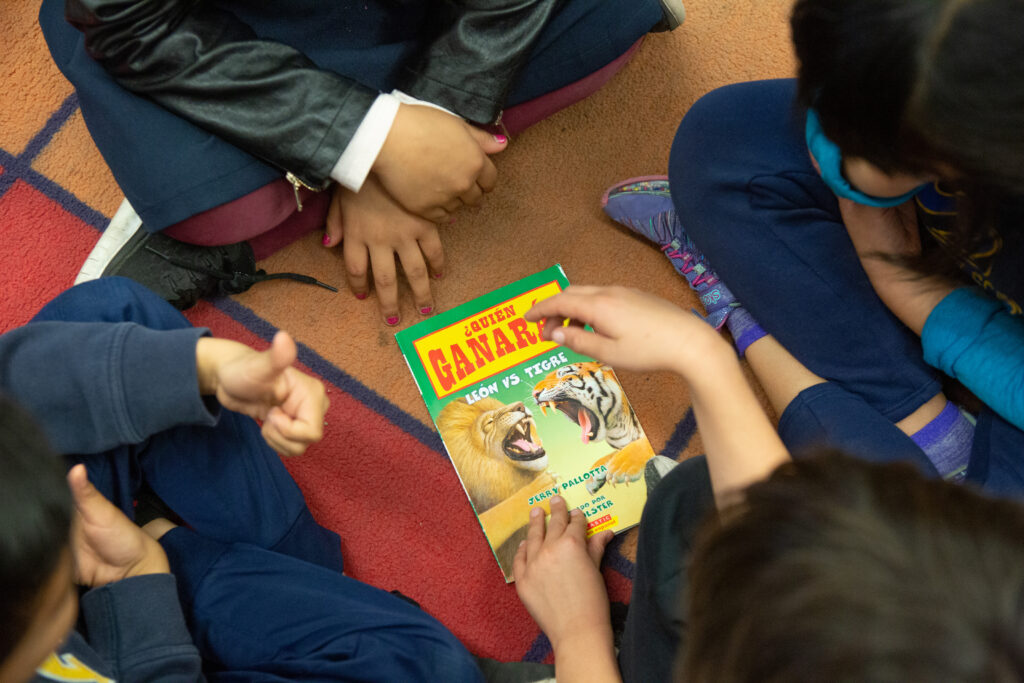

Credit: Allison Shelley / American Education

Imagine a cross-country road trip using outdated maps. What are the chances you’ll take the best routes or even get to your destination?

This is what’s happening in California classrooms. Teachers receive outdated tools to teach reading; consequently far too few students become motivated, competent readers and writers.

Our most disadvantaged students pay the steepest price. Only 2 in 10 low-income Black students in third grade are at least on grade level in English language arts. The same is true for 3 in 10 low-income Latino students, 2 in 10 English learners, and 2 in 10 students with disabilities. Overall, only 4 in 10 California third graders read on grade level.

Many factors, in and out of school, influence reading achievement. Schools cannot affect what they cannot control. But they can control how reading is taught. AB 2222, introduced by Assemblymember Blanca Rubio, seeks to update how schools teach reading. It would require that instructional reading materials, teacher preparation reading courses, and in-service teacher professional development all adhere to reading research, which the bill refers to as the “science of reading.”

English learner advocacy organizations opposing AB 2222 — the California Association for Bilingual Education (CABE), Californians Together and, most recently, the Center for Equity for English Learners at Loyola Marymount University — have voiced extreme objections to the bill with no hint of attempting to find workable solutions.

This is unfortunate. Because California’s teacher preparation programs provide insufficient attention to teaching reading to English learners, a concerted effort is necessary to address this and other policy shortcomings affecting these students.

Yet when Assemblymember Rubio, formerly an English learner and a teacher, called upon CABE and Californians Together to help draft legislation to serve every child in California, including English learners, the groups refused, citing a “philosophical difference.”

Philosophies aside, existing research could help teachers of English learners do a better job. Why would self-described advocates for these students walk away from developing solutions, choosing instead to deprive teachers and teacher educators of research knowledge to help students attain higher literacy levels? Whose interests are served? Certainly not students’.

Vague, misleading language and misinformation plague the field, most perniciously about the “science of reading.” The term is cited repeatedly in the bill but poorly defined.

Moreover, opponents of the bill are fond of labeling science of reading as one-size-fits-all, rigid, or a “magic pill.” It is none of these. Nor does it “isolate” phonics.

Anyone who knows anything about reading research over the past half-century knows these characterizations are simply wrong.

Many districts have indeed implemented poor practices such as excessive phonics instruction and insufficient attention to language, comprehension, vocabulary and knowledge development, all in the name of “science of reading.” This can’t be blamed on reading science. The culprit is misinformation, which opponents of the bill perpetuate.

I’ll try to clarify.

The science of reading — just as the science of anything — is a body of knowledge that informs how students develop reading skills and how we can most effectively teach reading (and writing) in different languages to monolingual or multilingual students. This science, based on decades of research from different disciplines and different student populations worldwide, shows that:

- While a first language is typically acquired naturally by being around people who speak it, written language (literacy) must generally be taught, learned and practiced. This is true for a first, second or later language.

- Literacy is extremely difficult, if not impossible, without foundational skills connecting the sounds of the language with the letters representing those sounds, what is typically called “phonics” or “decoding.”

- The best way to help children acquire foundational literacy skills is through direct, explicit and systematic instruction to help them develop accurate and automatic word reading skills. The practice known as “three-cueing,” where students are taught to recognize words using some combination of “semantic,” “syntactic” and “grapho-phonic” cues, is far less effective for most students, including English learners: It’s insufficiently explicit about how the sounds of the language are represented in print.

- Some students will require a great deal of explicit instruction; others will require much less. Instruction building on individual students’ strengths and addressing their needs is necessary.

- As they develop these foundational skills, and throughout their schooling, students need instruction and other experiences to develop oral language, vocabulary, knowledge and other skills. Accurate and automatic foundational literacy skills merge with these other skills, leading to skilled fluent reading and comprehension, both of which must be supported and improved as students progress through school.

- Although all this is true for students in general, some require additional considerations. For example, English learners in English-only programs (as most of these students are) must receive additional instruction in English language development, e.g., vocabulary, as they’re learning to read in English. English learners fortunate enough to be in long-term bilingual programs, continuing through middle and high school, can become speakers and readers of two languages — English and their home language.

Unfortunately, AB 2222 undermines its own cause by failing to articulate clearly what science of reading actually signifies. With some improvements, the bill could acknowledge what we know from research that is relevant to meeting the needs of English learners:

- How to help English learners having difficulty with beginning and early reading get on track, either in Spanish or English;

- How to help older English learners make better progress in their reading achievement by providing comprehensive advanced literacy instruction; and;

- How long-term bilingual education can pay dividends in terms of bilingualism, biliteracy and generally enhanced English language achievement.

It is difficult to pack all this into a piece of legislation clearly and precisely. But try we must if we’re serious about improving reading achievement rather than winning the latest reading wars skirmish.

We should get past the squabbling, turf protection and unhelpful language and instead do the right thing for all students. AB 2222’s introduction is an important step forward on the road to universal literacy in California. We must get it on the right track and take it across the finish line.

•••

Claude Goldenberg is Nomellini & Olivier Professor of Education, emeritus, in the Graduate School of Education at Stanford University and a former first grade and junior high teacher.

The opinions expressed in this commentary represent those of the author. EdSource welcomes commentaries representing diverse points of view. If you would like to submit a commentary, please review our guidelines and contact us.